As a diabetic you’ve likely been told that potatoes are not something you should be eating very often with your condition. At least not white potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), a frankly unjust denomination that does not even begin to accommodate the staggering 4-5000 different varieties that are currently being cultivated around the world. But you may have been told to consider adding the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) as a regular to your diet since it’s apparently so much better for you. But just how much better are sweet potatoes for diabetes compared to regular, white potatoes (and not just white)?

The truth lies somewhere in the middle. If you want to know which of the two potato varieties is a better option for you if you have diabetes, then you have to understand your condition. What is diabetes and what does it do to your body? Well, diabetes is a disease of the metabolism, more specifically of the metabolism of carbohydrates (a nutrient). In simple words, it affects how your body processes carbohydrates from plant foods (sugar is a carbohydrate too).

Under normal conditions, when a person eat plant foods, the carbohydrates in them are broken down into their simplest forms and absorbed to produce energy for the body to use. And said carbohydrates become glucose (sugar) in the bloodstream. At this point, cells in the pancreas make the hormone insulin to help move the glucose (sugar) from the bloodstream and into cells in the body, whether muscle or fat cells or somewhere else. But if the pancreas can’t make enough insulin (type 1 diabetes) or the cells of the body aren’t as responsive as they should be to it (type 2 diabetes), the sugar obtained from the digestion of carbohydrates stays in the bloodstream for too long. This is called hyperglycemia – too high blood glucose levels.

Over time, this situation is a source of ill health and causes damage to tissues and organs and all the diabetes-related health problems, from nerve damage to blindness to heart and kidney disease.

What can diabetics do? The first course of action is to manage their diets by limiting intake of carbohydrates both per day and per meal, choosing some plant foods over others and pairing plant foods with animal foods to reduce the effects of the first on blood glucose levels – basically making all the necessary dietary changes to stop the cycle of hyperglycemia. Medication may be required (always for diabetes type 1).

In order to prevent long-term side effects and even reverse diabetes type 2 in some cases, special attention must be paid to choosing your food. All plant food must be judged based on its estimated effects on blood glucose levels and consumed accordingly, whether this means more often or more rarely (or not at all). What nutritional indicators help us determine these effects? For plant foods, it’s carbohydrate content with its sub-categories – sugar, fiber and other digestible carbohydrates – and glycemic index and load values, also based greatly on carbohydrate values. All the other elements of nutrition fall second.

Just because one food is more nutritionally dense than a very similar one, that doesn’t automatically mean it’s better specifically for diabetes. The same is true for white and sweet potatoes: while nutritional aspects such as vitamin and mineral content matter, it’s the carbohydrates, sugar, fiber and glycemic index and load values that weigh the most for diabetic patients and impact their condition and its evolution to a far greater extent than the vitamins and minerals they contain.

With this in mind, saying sweet potatoes are better for diabetes because they are rich in beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A (and only in orange-fleshed varieties, mind you) or because they have good amounts of vitamin C (which is affected by cooking anyway), while not addressing the similarities regarding other much more important nutritional aspects is missing the point. The nutritional aspects that matter the most (carbs, sugar, fiber, glycemic index and load) put the white and sweet potatoes somewhat at a tie. The rest of the nutritional elements fall second place.

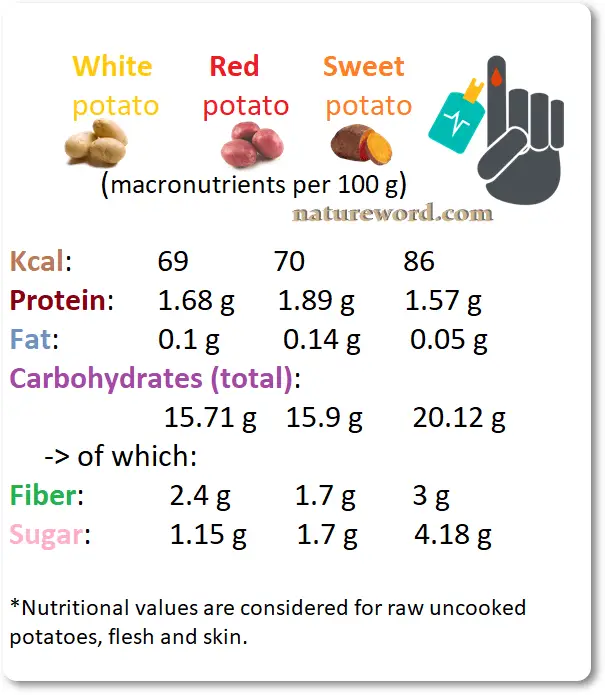

White vs red vs sweet potato nutrition facts

Nutritional values of white, red and sweet potato (raw, flesh and skin) for 100 g:

White potato: 69 kcal, 1.68 g protein, 0.1 g fat, 15.71 g carbohydrates of which 2.4 g fiber and 1.15 g sugar.

Red potato: 70 kcal, 1.89 g protein, 0.14 g fat, 15.9 g carbohydrates of which 1.7 g fiber and 1.29 g sugar.

Sweet potato: 86 kcal, 1.57 g protein, 0.05 g fat, 20.12 g carbohydrates of which 3 g fiber and 4.18 g simple sugars.

You may find it easier to compare nutritional values in the image below.

As you can see, macronutrient profiles are very similar which means eating either white potatoes or sweet potatoes will produce about the same effects in a diabetic patient and affect blood glucose metabolism roughly the same way. Limited intakes produce small changes in blood glucose metabolism, which is good for diabetes. But high intakes will definitely rise blood glucose levels fast, especially if the potatoes are consumed separately from other foods.

In other words, most diabetics can eat small amounts of white and sweet potatoes safely with their condition (preferably not everyday), but too high a intake of either variety is bad for diabetes from the start. The way the potatoes are cooked also impacts blood glucose metabolism in diabetics.

Boiled vs baked vs roasted. Whether it’s regular white or red potatoes or sweet potatoes that you’re eating, or planning to, experiments show boiled is always better. This has to do with glycemic index, a scale that measures how the carbohydrates in plant foods raise blood sugar levels. A glycemic index below 55 is low, between 55-69 moderate and between 70-100 high.

In the case of white (and red) potatoes, boiling then allowing the potatoes to cool down completely lowers their glycemic index by a lot, from over 85-90 to about 56 or even slightly below. Studies explain that when the potatoes cool down, the starches in them become more resistant to digestion which slows down the rise in blood glucose levels, hence the almost low glycemic index.

Roasted and baked regular potatoes are high glycemic, 70-90 on the GI scale.

In the case of sweet potatoes, boiling causes the glycemic index to drop to as low as 41-44 on the GI scale. Compared to the high glycemic index of raw sweet potatoes (70), the difference cooking makes is staggering. Roasted and baked sweet potatoes are high glycemic, over 80 and over 90.

According to experts, it’s better for diabetics to eat potatoes boiled rather than roasted or baked.

White or sweet potato for diabetes?

But which is better: sweet potato or white potato if you have diabetes? Overall, the effects of regular, white potatoes and sweet potatoes are comparable and the two can be used interchangeably in a diabetic diet, with the mention that they are important sources of carbohydrates and should be consumed in limited amounts, infrequently, as per every diabetic patient’s tolerance.

How much white and sweet potato can you eat safely with diabetes? Small servings of 100-150 g are recommended and no more than one serving a day. If needed, that one serving can be split into 2 or more even smaller portions to be consumed throughout the day, not in one sitting. Considering that one 100 g serving can easily provide 15-20 g of carbohydrates, both white and sweet potatoes are best consumed together with other foods, not separately. Ideally, green leafy vegetables with little effect on blood glucose levels and animal foods (meat, fish, eggs, cheese) make good pairs.

It helps to exercise afterwards and use up the carbohydrates you’ve just eaten. But if you don’t tolerate carbohydrates well at all and feel sick or unwell after eating potatoes, then consider not eating them at all and switch to other vegetables that do not elicit these effects from you. In any case, absolutely avoid pairing potatoes, whatever the kind, with high-carbohydrate foods or sugary options like chocolate or marshmallows.

Benefits of nutrients in potatoes

As for the vitamins, minerals and antioxidants in the starchy vegetables, while they do not provide major benefits specifically for diabetes, they do contribute to the nutrition of the diabetic patient in the same manner they contribute to the nutrition of the non-diabetic person as well as help with certain aspects of the condition.

1) Fiber helps regulates digestion and satiate, with minor benefits for weight management, as well as has light hypoglycemic effects.

2) Vitamin A from beta-carotene in orange-fleshed varieties of sweet potato helps with vision acuity (but needs fat to be absorbed).

3) B vitamins contribute towards healthy skin and a healthy nervous system, both areas of health affected by diabetes.

4) Magnesium and potassium are good for hypertension, a major concern in diabetics. Studies show magnesium also helps control blood sugar in diabetics.

5) Vitamin C is mostly lost with cooking, but together with zinc offers minor benefits for skin and has immuno-stimulating properties.

But none of these nutrients produce any significant, measurable, quantifiable effects for diabetics unless blood sugar levels are well managed, which consists of the basics such as reducing portion size, counting carbohydrates, eating clean, varied and balanced, according to the restrictions of a diabetic diet. All diabetes-associated health problems will still progress with continual hyperglycemia and no amount of one nutrient, whether beta-carotene or iron or something else will be able to counteract or reverse progression of the disease.